This art exhibition, which we visited at Tate Modern last month, introduced me to an artist I had only briefly known. It marked the first major retrospective of this artist in the UK in nearly 20 years.

Philip Guston, born in Canada to a Jewish immigrant family initially named Goldstein, grew up in the US. As a Canadian American artist, he employed various mediums, including painting, printmaking, mural, and drawing, earning recognition as one of the most influential American painters of the last century.

His early work comprised murals in the Mexican muralism style, collaborating with the renowned Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, and paintings, reminiscent of Picasso’s blue period, that addressed wars abroad and racism in America, drawing inspiration from consistent interests and concerns.

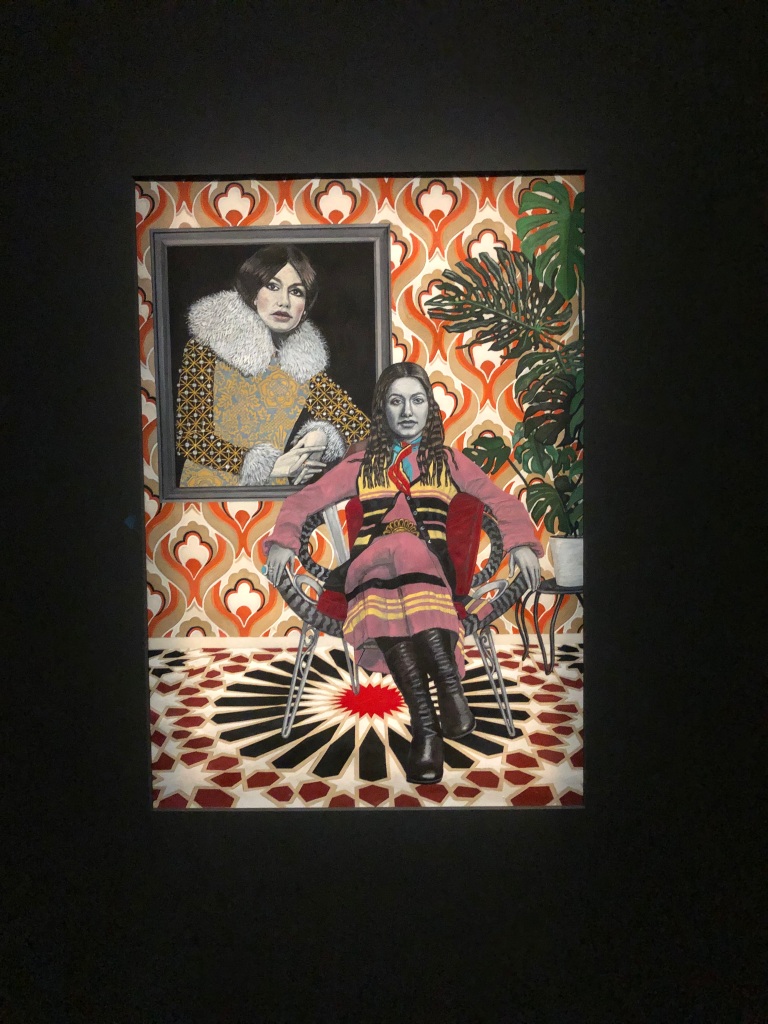

Guston achieved acclaim as one of the celebrated abstract painters of the 1950s and 1960s, standing alongside Mark Rothko and childhood friend Jackson Pollock. However, amid the social upheavals of the late 1960s, he criticized abstraction and shifted to large-scale paintings featuring comic-like figures, some adorned with white hoods as a representation of evil and the perpetrators of racism. This shift showcased his distinctive voice, establishing him as one of the most influential painters of the late 20th century.

For over 50 years, Guston created paintings and drawings capturing the turbulent world he witnessed. The traveling retrospective, co-organized by four museums, including Tate Modern, postponed its schedule for four years in 2020, citing that Guston’s work couldn’t be shown “until a time when the powerful message of social and racial justice can be more clearly interpreted.” The art world’s reaction, protesting with allegations like “How dare you postpone this show; everyone knows these paintings are against racism,” highlighted the controversial nature of Guston’s works.

While Guston’s art didn’t particularly resonate with me due to its obsessive focus on the surrounding evil, I appreciate that this exhibition introduced me to a very idiosyncratic artist. He developed his style alongside the major art movements of the past century, finding his voice as an activist-artist using his work as a tool to bring attention to crucial social issues. In today’s tumultuous times, marked by ongoing wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, Guston’s work remains relevant, reflecting the challenging realities of our era.

Pintando la banalidad del mal

Philip Guston

5 Octubre 2023 – 25 Febrero 2024

Tate Modern, Londres, Reino Unido

Esta exposición de arte, que visitamos el mes pasado en Tate Modern, me presentó a un artista que apenas conocía. Marcó la primera retrospectiva importante de este artista en el Reino Unido en casi 20 años.

Philip Guston, nacido en Canadá en una familia judía inmigrante originalmente llamada Goldstein, creció en los Estados Unidos. El artista canadiense-americano, empleó varios medios, incluyendo pintura, grabado, mural y dibujo, ganando reconocimiento como uno de los pintores estadounidenses más influyentes del último siglo.

Su obra temprana incluía murales en el estilo del muralismo mexicano, colaborando con el renombrado muralista mexicano David Alfaro Siqueiros, y pinturas, evocadoras del período azul de Picasso, que abordaban las guerras en el extranjero y el racismo en América, inspirándose en intereses y preocupaciones constantes.

Guston alcanzó la aclamación como uno de los pintores abstractos más destacados de las décadas de 1950 y 1960, junto a Mark Rothko y su amigo de la infancia Jackson Pollock. Sin embargo, en medio de las convulsiones sociales de finales de la década de 1960, criticó la abstracción y se volcó a pinturas a gran escala con figuras cómicas, algunas de ellas con capuchas blancas como representación del mal y los perpetradores cotidianos del racismo. Este cambio mostró su voz distintiva, estableciéndolo como uno de los pintores más influyentes de finales del siglo XX.

Durante más de 50 años, Guston creó pinturas y dibujos que capturaban el mundo turbulento que presenciaba. La retrospectiva itinerante, coorganizada por cuatro museos, incluido Tate Modern, pospuso su programación durante cuatro años en 2020, argumentando que la obra de Guston no podía mostrarse “hasta un momento en que el poderoso mensaje de justicia social y racial pueda ser interpretado más claramente”. La reacción del mundo del arte, protestando con alegatos como “¿Cómo se atreven a posponer esta exposición? Todos saben que estas pinturas son contra el racismo”, destacó la naturaleza controvertida de las obras de Guston.

Aunque el arte de Guston no resonó particularmente en mí debido a su enfoque obsesivo en el mal circundante, aprecio que esta exposición me haya presentado a un artista muy idiosincrático. Desarrolló su estilo junto a los principales movimientos artísticos del siglo pasado, encontrando su voz como un artista activista que utiliza su obra como una herramienta para llamar la atención sobre problemas sociales cruciales. En estos tiempos tumultuosos, marcados por guerras en curso en Ucrania y Oriente Medio, la obra de Guston sigue siendo relevante, reflejando las difíciles realidades de nuestra era.